The Legal Loophole

It's been an exciting time in my hometown of Millbury, as our Town Manager unexpectedly resigned last week. I was at my local Select Board meeting on Tuesday night to cover the transitional process for The Bramanville Tribune (cheap plug for my other outlet), but there was a secondary topic on the agenda that piqued my interest because of its overall alignment with the POST records project - the re-appointment of our town counsel, Mirick O'Connell.

I've gotten to know some of the legal firms that serve the municipalities of Massachusetts over the last few months. While some departments and towns handled their records requests on their own, many of the departments that didn't (initially) rely on shoddy advice from the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association instead leaned on contracted legal counsel to withhold the public records. This is not where my critique of the situation lies - after all, cities and towns pay good money to these firms to handle legal requirements and other assorted requests. The question I have is more about the quality of the work these towns are getting relative to the cost.

Millbury spends $100,000/year on general counsel services. In broad strokes, we don't pay Mirick O'Connell by the hour and they cover a host of issues that require legal support as a result. I worked directly with our assigned counsel on projects for boards I served on, and he was solid and responsive in ways I know other lawyers... aren't. The joke was made at the Tuesday Select Board meeting that we're definitely getting our money's worth as we negotiate the departure of yet another Town Manager, but there's some truth to the sort of consistency such services bring. We have a good deal here in town, all things considered.

The standard "check" on these sort of services? The Massachusetts procurement law. At a high level, the state puts detailed rules around the purchase of goods and services from outside vendors to ensure that proper oversight is in place. As conservative as I am (I know this newsletter is popular with abolitionist types, but someday you should ask me what I think about Elizabeth Warren), these sorts of state-level mandates and rules on agencies and vendors are necessary. Long and short, it puts some ol' fashioned American competition into getting the most for your tax dollar, and provides a transparent way to see who bid on what and what their proposed plans are.

Responding to these procurements is an art all its own, but is also quite an undertaking, which is at least part of why the procurement schedule is set up as it is. Again, high level, but if a procurement is under $10,000, you can just buy it; up to $50,000 an agency needs to solicit at least three bids; and if it's going to be more than $50,000, you have to put it out to public bid. Except when you don't.

Like with legal services.

As I noted above, the expenditure for town counsel in Millbury is $100,000. Under typical circumstances, we might expect this to then go to out to bid, but 30B has exceptions, and legal counsel is one of them. Cities and towns generally don't need to seek out bids for legal services - I learned that two days ago.

So what does this have to do with transparency? Besides the lack of a public bidding process - with some searching, you might find the contract online - there's no significant check or balance on their product. Your Select Boards, your City Councils, they're approving the contracts year after year even though they're not the ones engaging with the legal teams on a day-to-day basis. That's at least partially how, for example, K-P Law can hold contracts with a third of the state - the people approving these contracts aren't the ones experiencing them, and then when these law firms fail and fail and fail again, there's no consequence.

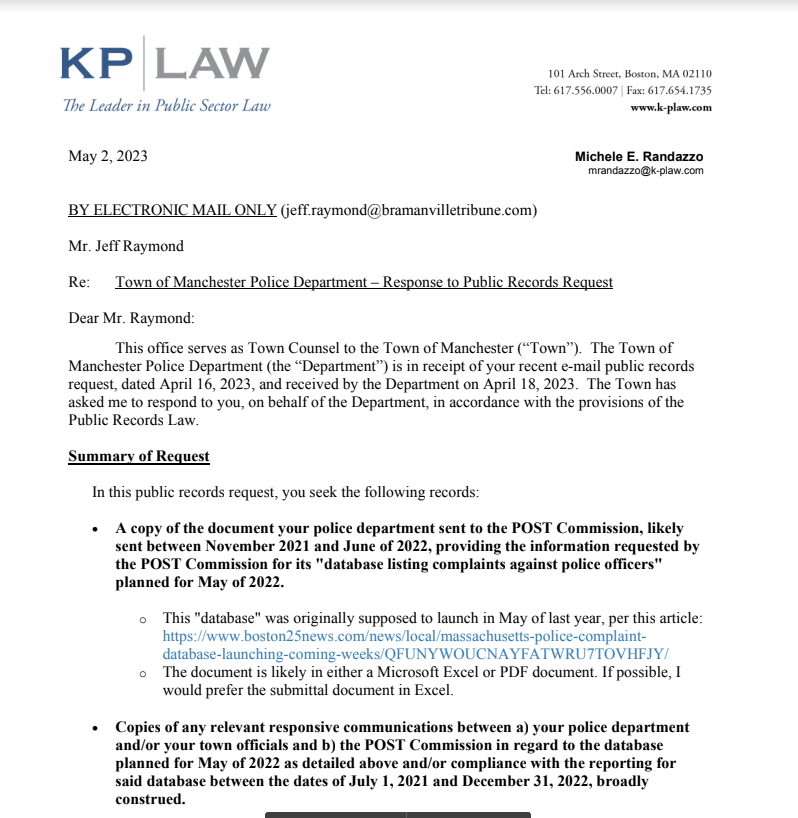

Take, for example, the letter I received from K-P Law on behalf of dozens of municipalities for my POST project - while I use the Manchester-by-the-Sea letter here, the letters were near-identical from other communities served by K-P Law. I quickly learned that not only was the firm seemingly working from a boilerplate text, but... well, let's just look at the meat of the letter:

After review of its records, the enclosed responsive charts submitted to POST Commission are being provided with this response at no charge, as a courtesy, on this occasion only. After an individual assessment of the records, please be advised that personnel information regarding specifically identified individuals contained in the enclosed charts submitted to the POST Commission by the Department has been redacted from the enclosed pursuant to Exemption (c) of the Public Records Law...

In this instance, the Town has carefully considered the application of Exemption (c) to the redacted charts enclosed, to determine whether disclosure of the information that has been redacted or withheld is such that the public’s right to know outweighs any individual officer’s privacy rights, and considered the factors set forth in the PETA case, cited above, as well as litigation pending in Massachusetts courts in the matters of Hovsepian, Scott et al. v. Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission, Suffolk Superior Court, C.A. 2284CV00906 and New England Police Benevolent Association, Inc., and Daniel Gilbert v. Massachusetts Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission, Suffolk Superior Court, C.A 2384CV00500. In balancing these interests, the Town has concluded that it is appropriate to redact certain personnel information from the enclosed charts under Exemption (c).

What is the problem with this, exactly? To take the skeptic's view, what does this independent journalist/researcher know that the highly trained lawyers don't? Well:

- Neither court case have anything to do with these records (and I'll have more to say on that in a future newsletter).

- The two cases were consolidated last year, and the legal firm doesn't appear to know it.

- Most significantly and most importantly, exemption (c) changed in 2020 to read "provided, however, that this subclause shall not apply to records

related to a law enforcement misconduct investigation."

The change in the public records law was, in part, to allow POST to collect and collate the disciplinary records, but also to ensure that the public has the right to access them. This is a critical point that these departments and a lot of the conversation surrounding these documents miss: you can establish POST without opening disciplinary records up to the public, and in fact the legislature could have done exactly that. Instead, they specifically carved out these records from the exemption in full.

Now, look back at what K-P Law provided, or find any community that relied on their guidance. At no point in time does the law firm ever acknowledge the deliberate change to the public records law. Are they trying to sneak it past us and hope we don't push back? Do they not actually know the law?

(The post-appeal contortions some lawyers have made once they're informed about the change are amusing, by the way - my favorites are when they try to default back to "no disclosure" even though the public records law explicitly assumes records are public unless there's an exemption.)

So why is this important and what does this have to do with transparency?

I'll point you back to the Hubbardston contract with K-P Law above. The cost for legal services in Hubbardston are $200/hr. Now, no two towns are alike, but if we assume $200/hr for these requests and assume anywhere between two-to-four billable hours for a request->response->appeal cycle, that adds up pretty fast. Sure, a town like Millbury that has $100,000 cover everything is going to eventually start bringing the per-hour cost down, but if, say, Rehoboth accepted the MTC contract for $180/hr and proceeded to force me to write three appeals for public records, we're talking around $1,000 just in that municipality.

Or if we do some very basic estimates, if we assume $300 per appeal (based on 2-3 hours of work and a better hourly rate - again, we're estimating) to towns with outside counsel, and let's say 250 appeals that required municipal counsel support from MassTransparency alone. That's $75,000 cities and towns have used to fight transparency.

$75,000.

To your municipality, $1,000 is a rounding error. In the aggregate? That's the salary and benefits for an experienced library director. That's a teacher. That's a few vehicles.

And for what? A Sisyphean effort to withhold public records using faulty logic and outdated boilerplate without any significant oversight from the taxpayers? When they could have simply released the records and been done with it?

It isn't okay, and I'm personally done pretending that it is.

A quick programming note: I'm on a new podcast, Lights Out Mass, with The Mass Dump's Andrew Quemere. The best way to get it is via his Substack, but we're up on Apple or Spotify. We have some guests lined up and we'll be talking a lot about public records and how they interact with our various projects and state operations, and whatever else. Would love for you to check it out and subscribe.

Jeff Raymond is a former columnist for the Millbury-Sutton Chronicle and Founding Editor of The Bramanville Tribune. He can be reached at jeff.raymond@masstransparency.org or on Twitter at @jeffinmillbury